By Rahab Gakuru

Nairobi, Kenya: Eriss Khajira, is a Kenyan journalist who tells the informal community’s stories to advocate for social change.

Every story she tells comes with the question, “what will be telling my story change?” Having been born in one of these communities, Eriss understands their concern.

The unique role of a journalist is to educate and inform the public on issues affecting their lives. Often, the question of whether a journalist should help resolve those issues pops up.

“I was born in Dandora slum. The place is a few meters from the Dandora dumpsite where thousands of people scavenge through the waste of Nairobi’s residents. I understand the struggles of living in a slum. I know what it’s like to choose between food or rent. I know what it’s like to never have enough. So, I understand the frustration of telling journalists your issues and they don’t offer solutions”, she says.

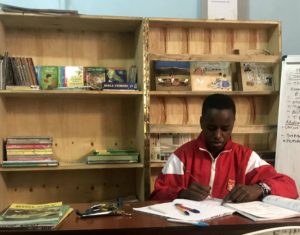

Eriss has gone hoping and in 2019, together with 7 others, they founded Big5 Library in Komarock Estate. The library is equipped with primary and high school books that are currently being used in public schools.

“I have done stories on education and the common challenge in slum is lack of resources like textbooks. A lot of children in slums lack textbooks, which limits their academic excellence. Children walk from one homestead to another looking for textbooks to do their homework wasting a lot of time and in the process pick destructive habits”, Eriss says.

Students from different schools visit the Big5 Library to do their homework. They also study ahead of the teacher to understand better and for good grades. “Currently the library is a few meters from the intended target, but this is because of the safety. “We have been looking for a safe place where we can set it up in either Kayole, Soweto or Umama slums,” Eriss says.

When the government announced the first COVID-19 cases, Eriss knew she had her work cut out. Armed with a camera Eriss visited Umama slum, a fairly new informal community with about 400 households. Lucy, a local shopkeeper narrates her fears and hopes in following the government guidelines on COVID-19.

“Currently we don’t have water. A 20 litres jerry can of water costs Ksh. 20 if you fetch it from the water vendors. They have a borehole. But you pay Ksh. 50 for the same if it’s delivered to your doorstep by cart pushers. There is nobody in this community who will pay Ksh. 50 just to buy water to wash hands.” She says.

According to Lucy, the government requires her to put water outside her shop for her customers to wash hands. “Buying water for my house use is difficult. I will need help to buy water and soap for my customers.” She adds.

Throughout her visit, Eriss noted different households were faced with similar challenges as Lucy’s. According to Eriss, social distancing in the slums is difficult to enforce because there are families with over five members sharing a single room. “Water supply in slums varies once a week.

But they could also go for two weeks without receiving any water. Families have to decide whether to buy water to wash hands or water for household use like drinking, cooking, bathing, and laundry. No family was going to prioritize buying soap and water to regularly wash their hands.” She adds.

After documenting several stories, Eriss, through Big5 Library in partnership with The Healthy Teeth Foundation, and Mathare Youth Sports Association (MYSA) decided to offer a little support to this community. “When I was young, my mum and I used to make liquid soap. So, I thought if I made it and distributed it to families that would be less one thing they had to worry about.” She says.

The big5 library started making soap and distributing it in Umama slums, Kayole, Soweto slum, and Mukuru slums for free. They targeted local shops, mothers, and green groceries.

Eriss says that every time they visited the residents would ask for water and masks. “So, we modified jerry cans to act as wash stations and set them in strategic public areas with a lot of movement. We also started to supply water using a water bowser. Every week we visit the wash station to refill the soap and water, which would be divided between needy households and wash stations.” She says.

Big5 Library would sell some of this liquid soap to help in running the project. They would also distribute free masks. During this visit, they would explain to the residents the importance of ensuring COVID-19 doesn’t find its way into the community.

“We feared that if one resident got infected the congestion would intensify the spread. So, we would constantly tell them the importance of keeping distance and washing hands as many times as they could. We are happy with the results because it’s been 5 months since the first case was announced in Kenya and the slum communities are doing really well with only 18581 reported COVID-19 cases countrywide and 299 deaths.” Adds Eriss.

According to Eriss, the residents are also not wearing the masks properly. They hang them on the chin while others put them in their pockets until they see the police. “I receive calls from families and children’s homes requesting food aid.

“As Big5 Library we are doing the best to help, but social distancing is our main challenge. Whenever we visit with food or water people start to gather to see what’s happening.” Eriss says.

Eriss is aware that the government banned uncoordinated direct distribution of food and non-food donations in vulnerable communities after it sparked a stampede in Kibera, Kenya. And instead request those willing to offer support to channel it through the Kenya Covid-19 Emergency Response Fund, in Nairobi, and the offices of governors and county commissioners in counties. So, she makes it her point to work with local authorities whenever she intends to offer any support to the informal communities.

Big5 Library has very limited resources and can only support about 100 families. So, to make this sustainable they started to teach groups how to make soap, which they sell to neighborhoods because it is multipurpose and is sold at a lower cost than bar soap.

“We have taught the Kayole Starlets, who are in the Kenyan Women Premier League how to make liquid soap. With the football matches paused at the moment and they need to make a new way to make an income.” Eriss says.

Big5 Library is supported by My Book Buddy, Booksteps, Sams Foundation, and Yoga Heart Kenya. In the future, they hope to acquire a bigger space in the informal community. Currently, they are not letting the children who have been on school break for the last five months in the library because of limited space to social distance.

The library has also partially been turned into a production center for liquid soap and wash stations. Eriss finally says when telling the informal community story, it’s important to not only focus on their struggles but also win.

In the slums, you will find the most extraordinary talents and innovations. By informing the world about them, then, they can get opportunities and resources to thrive.

In 2014, Eriss, debuted her first film Dusty Bin Dreams, a story that takes her back home to the largest dumpsite of East Africa: the Dandora dumpsite. Thousands of people live on and around this dumpsite, scavenging through the waste of Nairobi’s residents.